Personality Tests *Are* Horoscopes for White-Collar Professionals! (Part 2)

Results from comparing the MBTI, Enneagram, and DISC Assessment vs. astrology • Your personality is a gemstone, not a label • Psychometric tests and astrology: a case study in convergent evolution

Last week, we told the story of how one of us accidentally disproved astrology by following the wrong horoscope. We then conducted a single-blind, controlled experiment prank on readers to test how three psychometric tests (widely used in leadership training and pre-employment screening) would stack up against astrology. We’re calling it a “prank” instead of an “experiment” because we uh…forgot to seek approval from an institutional review board before turning our readers into human test subjects.

Whoops 😅

Drumroll, Please…

Here are the results from last week’s prankxperiment, along with citations. Proof that we didn’t just make all this up!

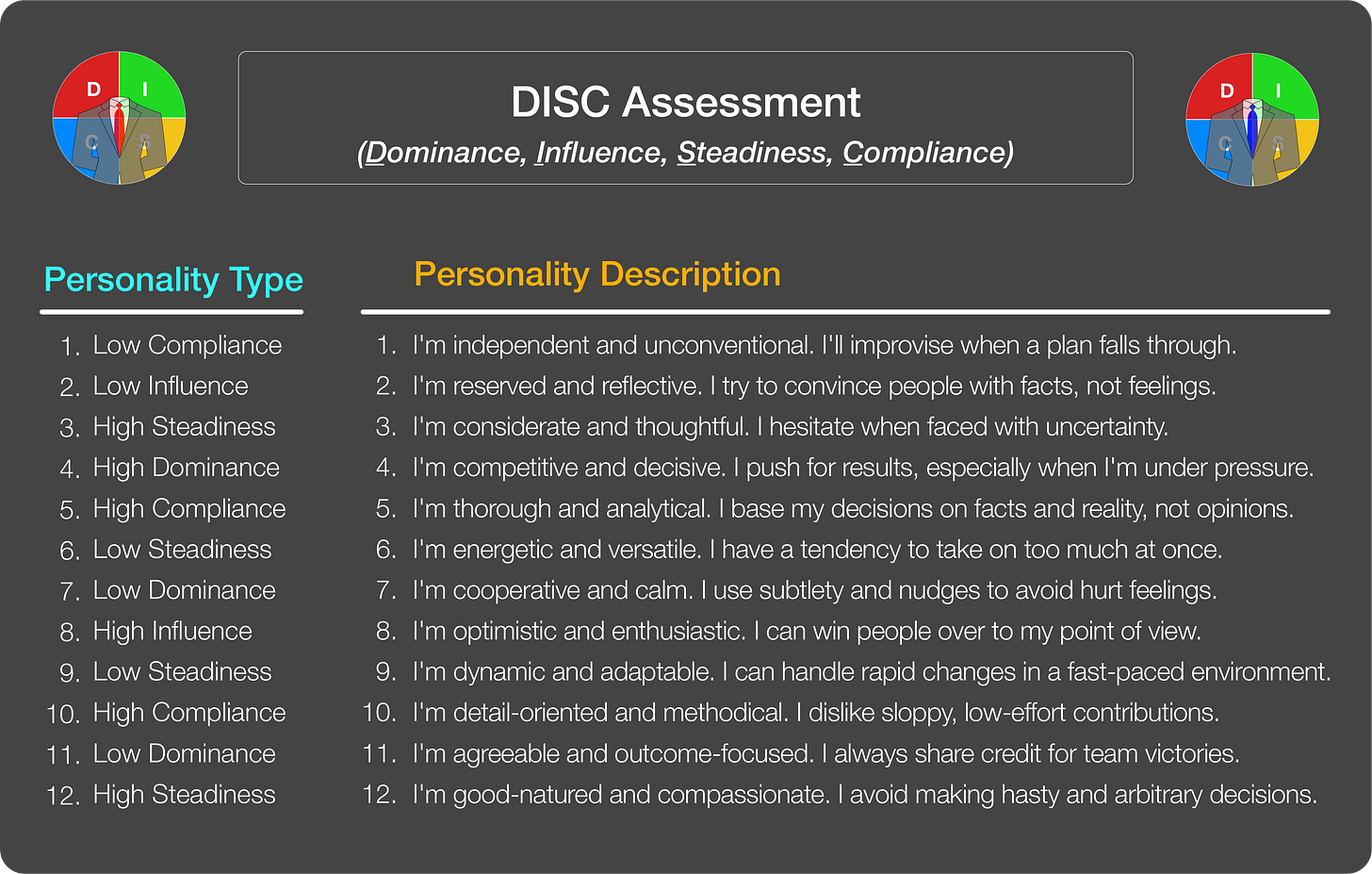

Mystery Test 1: DISC Assessment

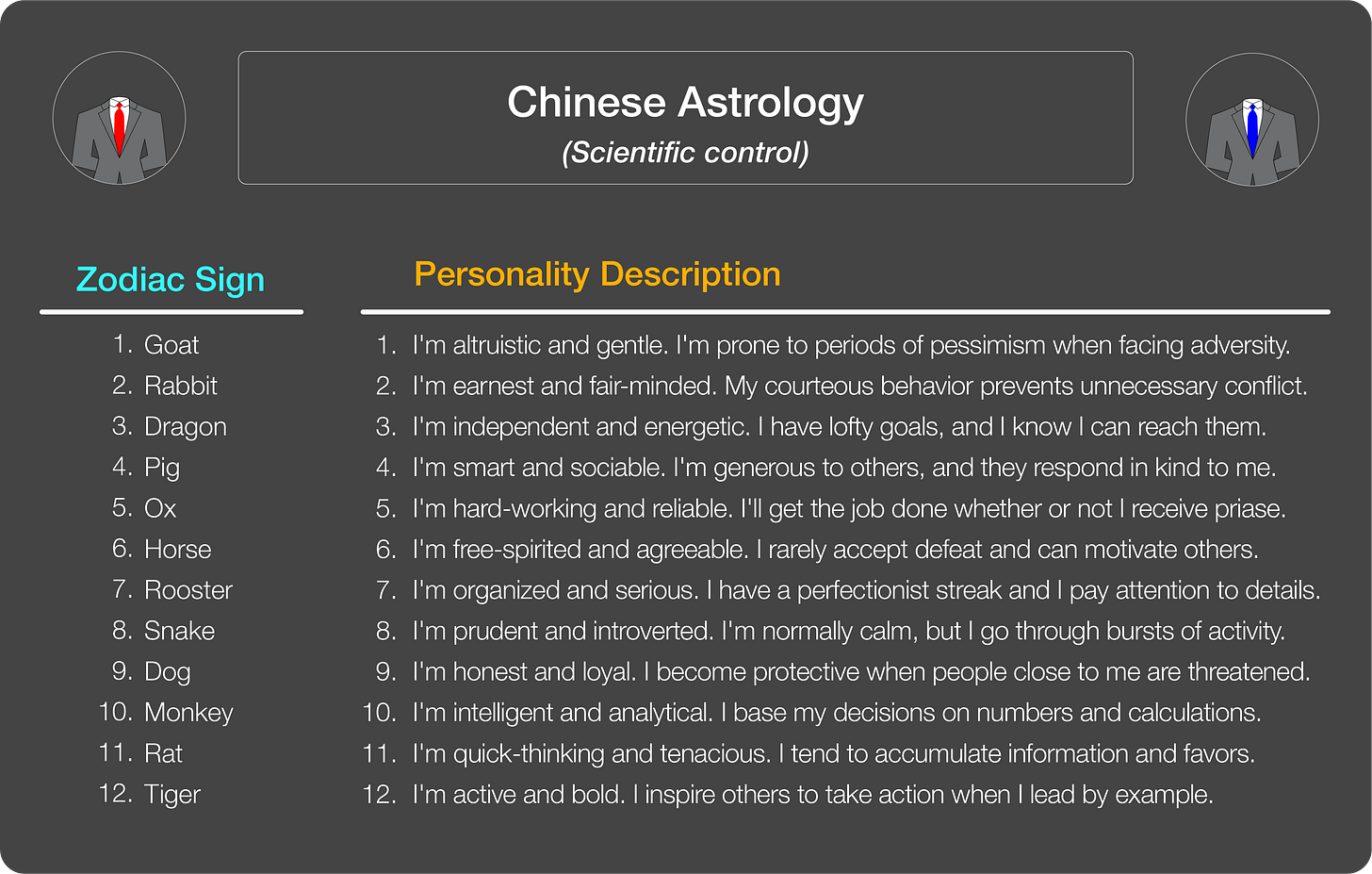

Mystery Test 2: Chinese Astrology

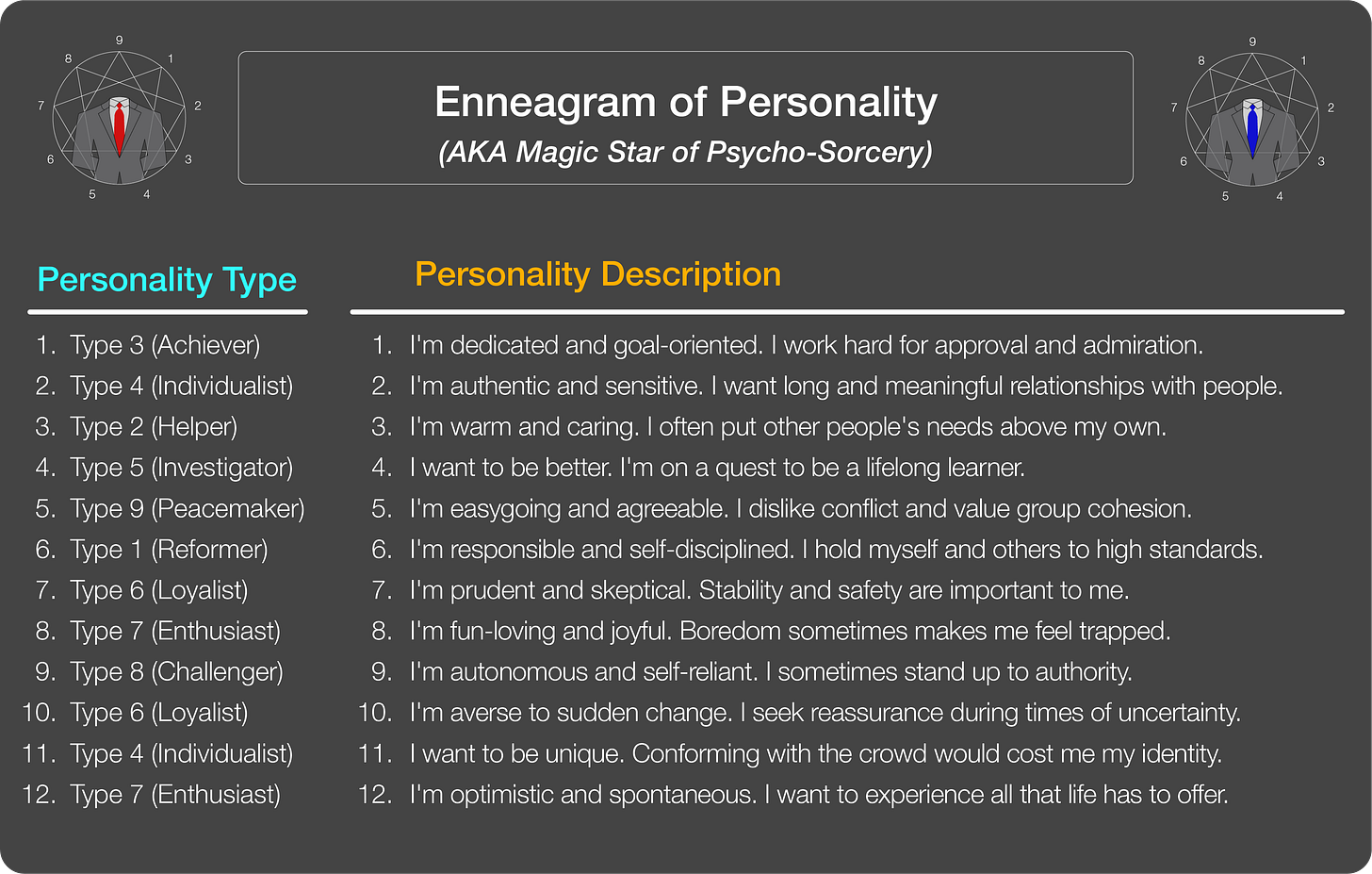

Mystery Test 3: Enneagram of Personality

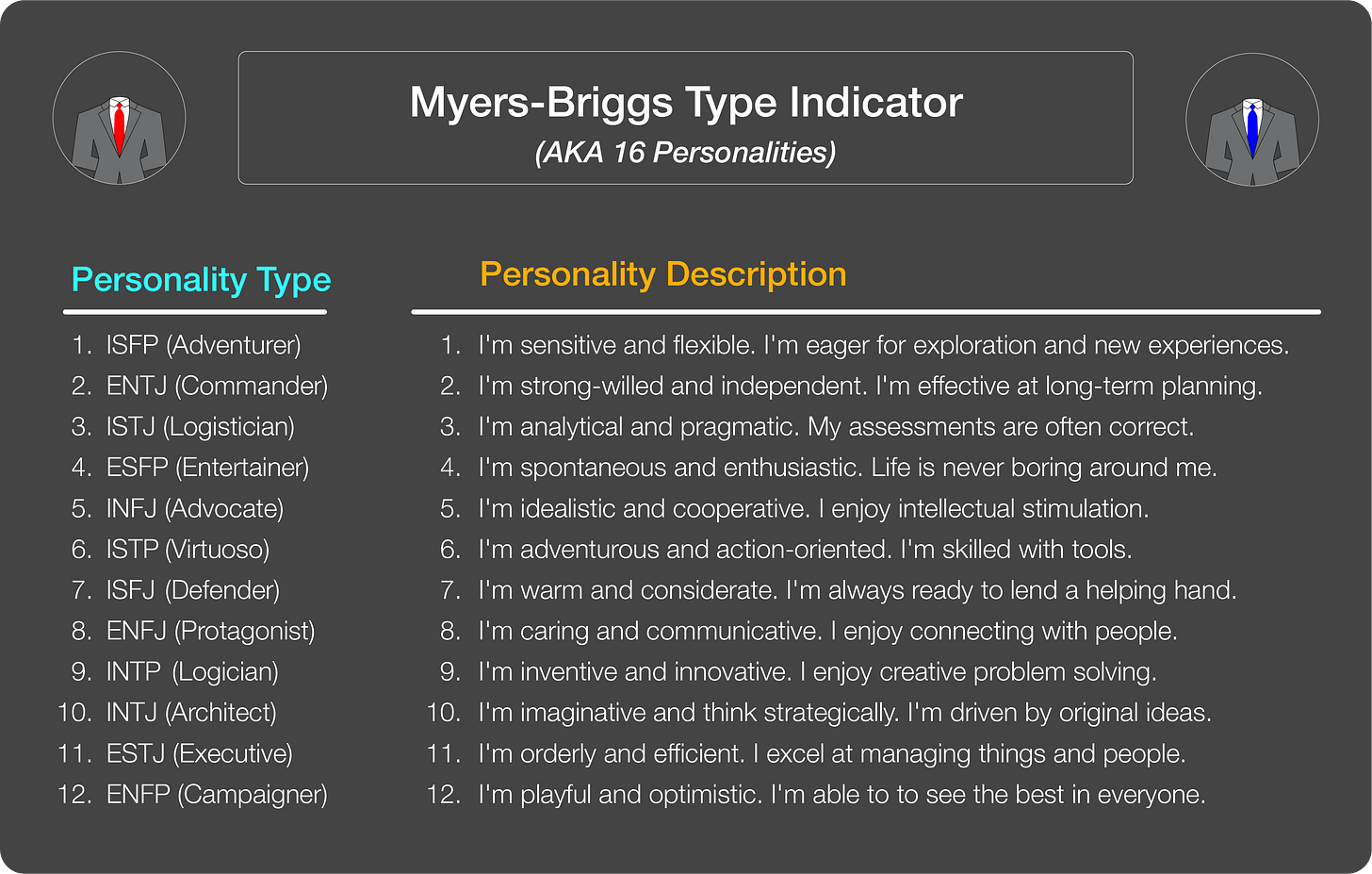

Mystery Test 4: Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

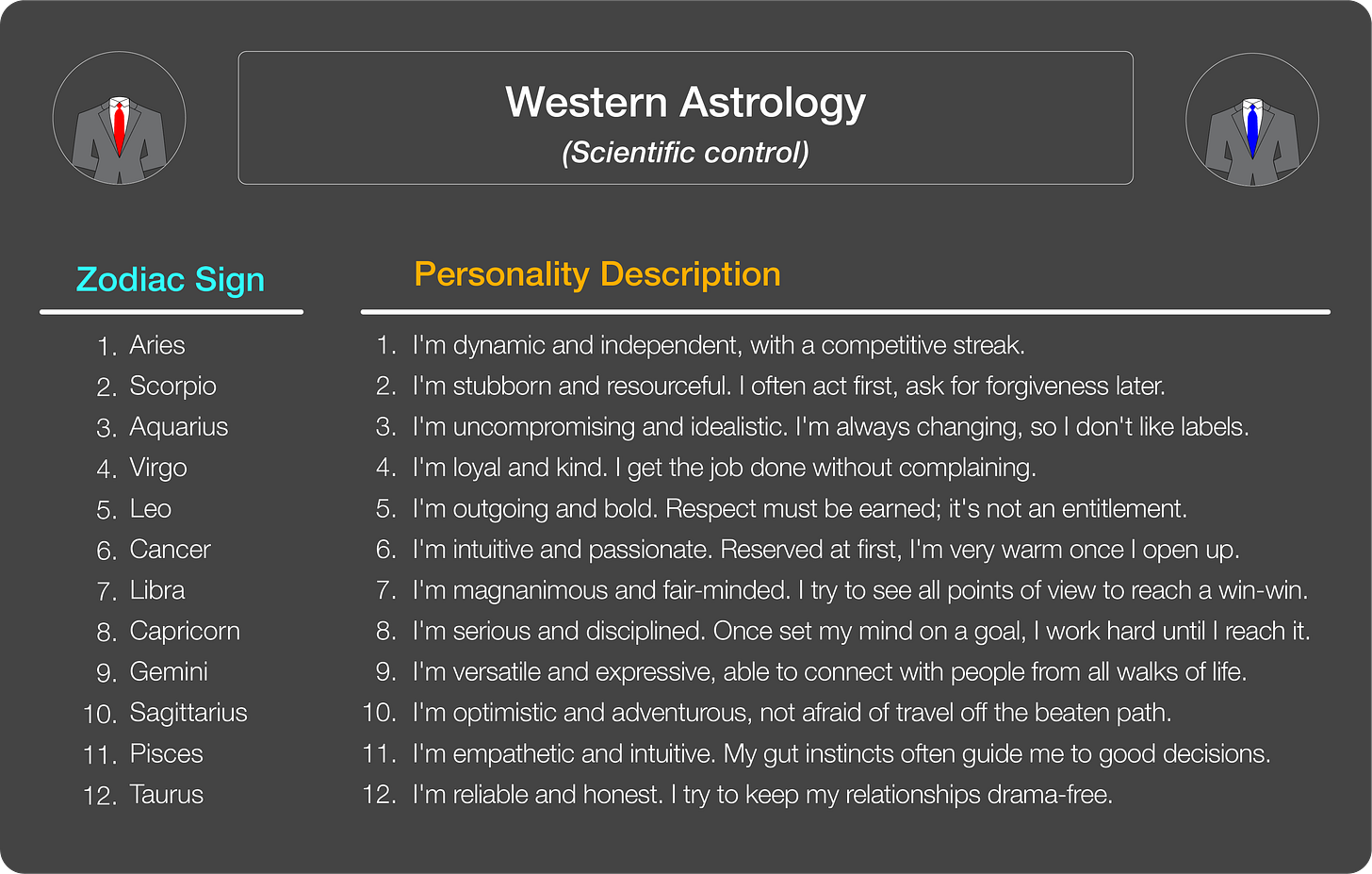

Mystery Test 5: Western Astrology

Discussion Monologue About the Test Results

Note: if this were an academic paper, this section would be labeled “Discussion.” It’s a weird choice of words because there’s no two-way dialogue between the authors and reader; just a bunch of nerds dictating the results at a computer screen. If you’d like to turn this monologue into a discussion, talk to us in the comments below! Or reply directly to the emailed newsletter. We could use some peer reviewers.

When we administered the mystery tests to ourselves last week, the horoscopes were indistinguishable from legitimate psychometric tests. We identified with at least half of the descriptions in every test. For several tests, we identified with more than 9 out of the 12 personality descriptions (>75%)!

Looking at the uncovered results this week, we feel that our assigned personality types and zodiac signs are reasonably accurate reflections of who we are. However, identifying with one type/sign did not preclude us from identifying with the others. No single personality type came close to describing the breadth of our behavior.

Our personalities are multifaceted gemstones

There are many metaphors for describing someone’s personality, but our favorite one is that of a cut and polished gemstone. Most facets of someone’s personality remain dim and dormant until circumstances cause facets to light up. Take the primary author of this essay, for instance:

When I’m writing, I alternate between my playful (ISFP/Type 7/Low Compliance) and analytical (INTJ/Type 5/High Compliance) facets. That’s why some articles contain more jokes than substance, while others are drier but more profound.

Under time pressure, my taskmaster facet flares to life. I become laser-focused (ESTJ/Type 3/High Dominance). My sense of humor evaporates like a whoopee cushion thrown into a volcano.

When my subordinates suffer misfortune, my solicitude facet glows warmly (ISFJ/Type 2/Low Dominance). Can you imagine being efficient with someone who lost a family member? “Please re-schedule your sobbing for the designated grieving period between 11 A.M. and noon o’clock.”

Public speaking activates my performance facet, turning me into an ENFJ/Type 4/High Influence stage actor1. Afterward, I retreat to my hidey-hole (or a restroom stall if personal space is unavailable) to recharge my social battery.

Different people light up different facets of my personality. I react one way to a boss whose presence sucks the fun out of every room, and another way to a different boss who’s self-deprecating and sociable.

If this weren’t complicated enough, my behavior is also influenced by internal factors such as emotional debris carried over from earlier in the day, hunger, horniness, fatigue, and which side of the bed I fell out of that day. I also behave differently due to external factors like pet peeves, comfort/discomfort, resource constraints, time pressure, and the mood of people around me.

If my personality is a gemstone, then my actual behavior is the kaleidoscope of colors that emerge from the gemstone when it’s taken into different environments. You’re the same way. Your personality is your gemstone, and your behavior is the kaleidoscopic light that shines through in response to different contexts.

If a single personality and its emergent behaviors are so complex, why would anyone try to pigeonhole themselves (or another person) into a single personality type that doesn’t overlap with other types? To answer that, let’s figure out…

Why the Personality Tests were Indistinguishable from Astrology

Once you meet enough people, you’ll start to notice behavioral patterns that are:

Repeated by one person, time and time again. For example, Howard from R&D tends to hide in the introvert’s corner at every party, picnic, and conference.

Repeated by multiple people who don’t know each other. You might notice that your cousin Stacey is a kindred spirit to Aliyah from the sales department – both are effusive, gregarious, and have more LinkedIn connections than Genghis Khan had offspring.

Once you notice these patterns everywhere, wouldn’t it be a valid scientific pursuit to catalog your observations? That’s what Carl Linneaus did when he started taxonomifying everything with scientific names, like Homo sapiens. Why not carry Linneaus’ torch into psychology? We could classify Howard from R&D as Homo sapiens psy. INTP Type 5-C. Stacey and Aliyah would be Homo sapiens psy. ESFJ Type 7-I. After all, isn’t it important for leaders to understand different human personalities and how they might be aligned or misaligned with each other?

Of course it’s important! That’s why astrologers have been attempting the same feat for over 3,000 years based on how the stars and planets are aligned or misaligned with each other. Horoscopes and personality tests were created to achieve a common goal, leading both down convergent paths. Some examples:

Western and Chinese astrology both use 12 zodiac signs to categorize people born under them. The Myers-Briggs personality test has 16 categories, the Enneagram has 9, and the DISC assessment has 8 to 12 depending on how you treat the four characteristics. The sweet spot seems to be around ~12 categories; it’s enough to provide an interesting variety, but not so many that the menu of options becomes overwhelming.

With only a dozen categories to choose from, horoscopes and psychometric tests are too reductionist to check for rare aspects of someone’s personality that you’re really interested in. Your pre-employment test won’t measure an employee’s ability to generate sales or patents, nor will it detect someone’s propensity to light a school bus full of children on fire while cackling like a homicidal maniac.

Horoscopes and psychological tests are frequently used to gauge human compatibility. Should someone born in the Year of the Dragon marry someone born in the Year of the Monkey? Would a business partnership between a Sagittarius and a Scorpio lead to prosperity or bankruptcy? Would hiring an ENTP add a complementary personality to a tight-knit crew of ISFJs, or steer the ship into the Straits of Conflicting Interest?

The magic is in the mystery

For thousands of years, astrology and horoscopes were part of the Institute of Conventional Wisdom. Famous astronomers like Kepler, Galileo, and Tycho Brahe were professional astrologers. Horoscopes make a lot more sense if you believe the earth is the center of the universe, as many people did before the Renaissance.

After witnessing a terrifying event like a blood moon or the sun transforming into a glowing black void, it’s natural to watch the skies carefully and attach special significance to planetary alignments and misalignments. People used to regard astrology like we regard string theory or machine learning today: an esoteric realm shrouded in mystery. Adherents and skeptics debated the merits and shortcomings of astrology, while the uninitiated busied themselves with mundane things like feeding themselves or dying from the bubonic plague.

Then came the smartypants Copernicus and Galileo, who dared to suggest the earth revolved around the sun, not the other way around. Their scientific logic was a gust of frigid air that blew away astrology’s aura of mystery. Stripped of mystique, horoscopes cease to be magical prophecies; they devolve into nonsense written by someone reading too much into mundane coincidences (“planet X happens to be in front of the constellation Y, therefore you should divorce your spouse”).

What the Institute of Conventional Wisdom considers to be legitimate knowledge has changed over the millennia. Alchemy has matured into chemistry. Spontaneous generation has given way to cellular biology. Multiple competing explanations for the puzzle “where do mountains come from?” have been superseded by plate tectonics. Astrology and horoscopes have been replaced by astronomy.

What about personality tests? Are they scientifically valid in all the ways that astrology was not? Or do psychometric tests merely give us another excuse to read too much into mundane coincidences (“employee X happens to be personality type Y, therefore we should fire him”)?

What Does the Evidence Say?

To recap from earlier in the article:

We found the personality descriptions indistinguishable from horoscopes.

We identified with at least as many personality descriptions as with horoscopes, sometimes more (looking at you, Enneagram ಠ_ಠ)

We have multi-faceted personality gemstones that cannot be adequately described by slapping a label on its biggest facet.

We suspect that most readers would agree with all three statements. That means personality tests don’t produce results that are much better than astrology. They belong in the west wing of the Institute of Conventional Wisdom, in the Tower of Corporate Astrology. The Tower rises above the Fog of Uncertainty, providing visitors with a comforting sense that they’ve domesticated the unknown.

But what if personality tests made me a better leader?

We didn’t claim that personality tests are garbage. We didn’t claim that the Myers-Briggs test, Enneagram, or DISC Assessment were wrong. We only compared psychometric tests to astrology and found them to be no better than horoscopes.

In last week’s post,

recounted a thoughtful personal story about how a 72-question personality survey made him a better leader. Upon discovering that his personality type was only shared by ~4% of the population, he had an epiphany: he had been managing others how he would like to be managed, which implicitly assumed that other people had personality types like his. If he hadn’t taken the personality test, he would’ve missed the valuable insight that other people’s personality gemstones are different from his – sometimes incomprehensibly different!So clearly, personality tests can do good. Does that mean pseudoscientific horoscopes are also capable of doing good?

Yes! In the next article, we’ll cover how the placebo effect can positively impact the lives of personality test users and astrology practitioners. Remember that one of the authors is an ex-believer in astrology; I still remember how it gave me a sense of control during a tumultuous time of my life. I only stopped believing when I realized my solace arose from false certainty.

That leads to a second question: are personality tests and astrology capable of doing harm?

Yes. We’ve seen people misuse their test results in real life, like making hiring or firing decisions based on the outcomes of psychometric tests. Our personalities are multi-faceted and complex, so slapping an ESFP or Type 8 or High Steadiness label on that person is the same as stereotyping them.

It’s illegal to discriminate based on racial, religious, or gender stereotypes.

It’s legal but usually unethical to discriminate based on beauty.2

It’s legal to discriminate based on personality stereotypes…but is it ethical?

Let’s explore these questions in the next article: How Leaders Can Use Personality Tests for Good, Not Evil.

Assuming I have time to prepare. For extemporaneous speeches, I devolve into whatever personality type describes a “nervous trainwreck who mumbles half-baked thoughts.”

In that post, we gave several examples of when it’s not only ethical but mandatory to discriminate based on beauty. For Adventures in Leadership Land readers who hire white-collar knowledge workers, discrimination based on beauty is generally a bad idea.